Inside Grand Seiko’s 9SA5 and 9SA4 Calibers

Editorial

Inside Grand Seiko’s 9SA5 and 9SA4 Calibers

Grand Seiko has always defined itself by an unusual combination of virtues: watches that are not only made to the highest possible standards of quality and beauty, but also meant to be worn every day, with the precision, reliability, and, at least in relative terms, affordability that such a role demands. That foundation remains unchanged. What has changed is the scope of the watchmaking itself, which has become more technically ambitious. The Kodo Constant-force Tourbillon is the ultimate statement of that intent, but the brand has also done something that might be rarer than the pursuit of any complication — the invention of a new escapement.

The self-winding Caliber 9SA5 and its hand-wound sibling, the 9SA4, are Grand Seiko’s most ambitious leap in fundamental mechanical watchmaking to date, each built around the Dual Impulse Escapement, whose greater efficiency underpins their combination of a high beat rate and extended power reserve. Both movements are assembled at Studio Shizukuishi, the dedicated home for Grand Seiko’s mechanical watchmaking in Iwate Prefecture. Opened in 2020, the facility is part of Morioka Seiko Instruments’ manufacturing site and continues the work that began under Daini Seikosha, once one of Seiko’s two factories. It is here that every mechanical Grand Seiko is assembled, adjusted, regulated, tested and finally cased.

- Caliber 9SA4

- Caliber 9SA5

In the stillness of the Shizukuishi forests in Iwate Prefecture, the Grand Seiko Studio Shizukuishi where every 9S mechanical movement is assembled, adjusted and regulated.

The Ideals Behind the Calibers

During my visit to the manufacture last year, Yuya Tanaka, designer of the Caliber 9SA4, explained that Grand Seiko conceives of its mechanical movements in terms of three essential tenets: beauty, precision, and long power reserve. A movement, he said, is considered ideal only when all three are present. It is a simple formulation and one that could be mistaken for marketing rhetoric if you let it pass too quickly, yet it became harder to forget the longer I turned it over in my mind. The very act of having a focus, and of defining it in those particular terms, seemed to me unusually alluring, and I found myself wondering how many movements out there could genuinely satisfy that triad without reservation, namely without recourse to silicon components or the brute-force solution of an oversized caliber.

The difficulty, as always, lies in the physics. Short of introducing silicon or enlarging the mainplate, the pursuit of longer autonomy often comes at the expense of precision. To extend the power reserve is to ask more from the mainspring, and the balance must inevitably give ground by running at a lower frequency or shedding inertia. Reconciling the two without caveats, in short, is a demanding task.

Beauty, by contrast, is the most subjective of the three tenets, yet in watchmaking, it is no less tangible for being so. It resides in the logic of its architecture, in the design of its most ancillary components, in the shape of its bridges and the way light finds its way across their surfaces. Save for the work of the Micro Artist Studio and Atelier Ginza, the majority of Grand Seiko’s movements are produced on a relatively industrial scale; thus, finishing here is not typically the product of leisurely handwork with Gentian pithwood or burnishing tools, but there is still a tremendous amount of manual processes involved, on top of meeting the challenge of doing so at scale and with unfailing consistency. Achieving beauty without regard for time or cost is an idealized conception of quality that collectors and watchmakers alike have leaned on but which, historically, has never been the whole story. Industrialization has always been part of horology, and constraints have always defined what quality looks like in practice. To meet them is a matter of discipline and intent, and every step of the process has to be thought through with uncommon wisdom and care.

Taken together, these ideals create a set of demands that are anything but easy to reconcile: a movement that must be long-running yet high-frequency, efficient yet elaborate, and beautiful despite industrial production. In the 9SA5 and the 9SA4, it is precisely the coexistence of those contradictions that gives them their particular fascination.

Five years on from its launch, the 9SA5 has settled into the landscape of modern watchmaking, no longer a novelty but a proven caliber. My own runway has been shorter; since 2023, I have lived with it in the SLGH013, and since last year with its hand-wound sibling, the 9SA4, in the SLGW003. Yet, it has been long enough to notice certain qualities of the caliber that I never did before. Hence, it seems like the right moment to return to it in writing.

The Dual Impulse Escapement

The Dual Impulse Escapement, as it hardly needs repeating, but is still worth mentioning, is the second alternative to the Swiss lever to reach industrial production since Omega introduced the Co-Axial in 1999. More recently, Rolex has introduced the Dynapulse, a silicon double-wheel escapement, which brings the total to three escapements that have been designed with the aim of industrial production in more than two centuries since the invention of the lever escapement.

The lever escapement, which today beats at the heart of the overwhelming majority of mechanical watches, was invented by Thomas Mudge around 1754. Its lasting success in watches rests on the fact that, unlike the detent escapement, the balance receives an impulse at each vibration (twice per oscillation), which makes it inherently less susceptible to external disturbances. At the same time, unlike the older frictional-rest escapements, such as the duplex or the cylinder, the balance is not shackled to the escapement throughout its swing. Instead, it runs free after each impulse, traversing a supplementary arc unencumbered by any mechanical interference from the going train, and in so doing, it comes closer than its predecessors to the ideal of a harmonic oscillator. Add to this the fact that its construction is straightforward, robust, and adaptable to mass production, and it becomes the recipe for the single most enduringly successful escapement in watchmaking history.

Yet, as with all things in horology, there is a trade-off. Each impulse is delivered indirectly through the lever, and the escape wheel teeth slide across the pallet stones to transmit energy. This sliding contact does introduce friction, though in practice it is relatively minor. The greater loss comes from the indirect nature of the transmission. Because the impulse is routed through an intermediary, only part of the escape wheel’s motion is converted into useful torque on the balance.

Animation of a lever escapement, showing motion of the lever (blue), pallets (red), and escape wheel (yellow). (Image: Wikipedia)

Another consequence is that the fork cannot be perfectly symmetrical. The geometry is set up to favor equal locking, at the expense of equal impulse. The entry and exit pallets do not transmit exactly the same magnitude of impulse to the balance, though both are transmitted in the same way — through the lever.

Then there are escapements that deliver two impulses directly to the balance at each oscillation — the natural and the independent double-wheel escapement — but they introduce characteristic problems of their own that are simply not conducive to industrial production.

Between these extremes lies the hybrid approach, in which one impulse is delivered directly to the balance while the other still passes through a lever. This is the principle of both the Co-Axial and the Dual Impulse Escapements. By transmitting energy without the use of a lever they improve efficiency compared to the Swiss lever. But they also introduce a new layer of asymmetry. The direct impulse is clean, the indirect one less so, and at low torque, one side tends to falter before the other. That imbalance can cause the escapement to stop prematurely while the mainspring still has usable energy.

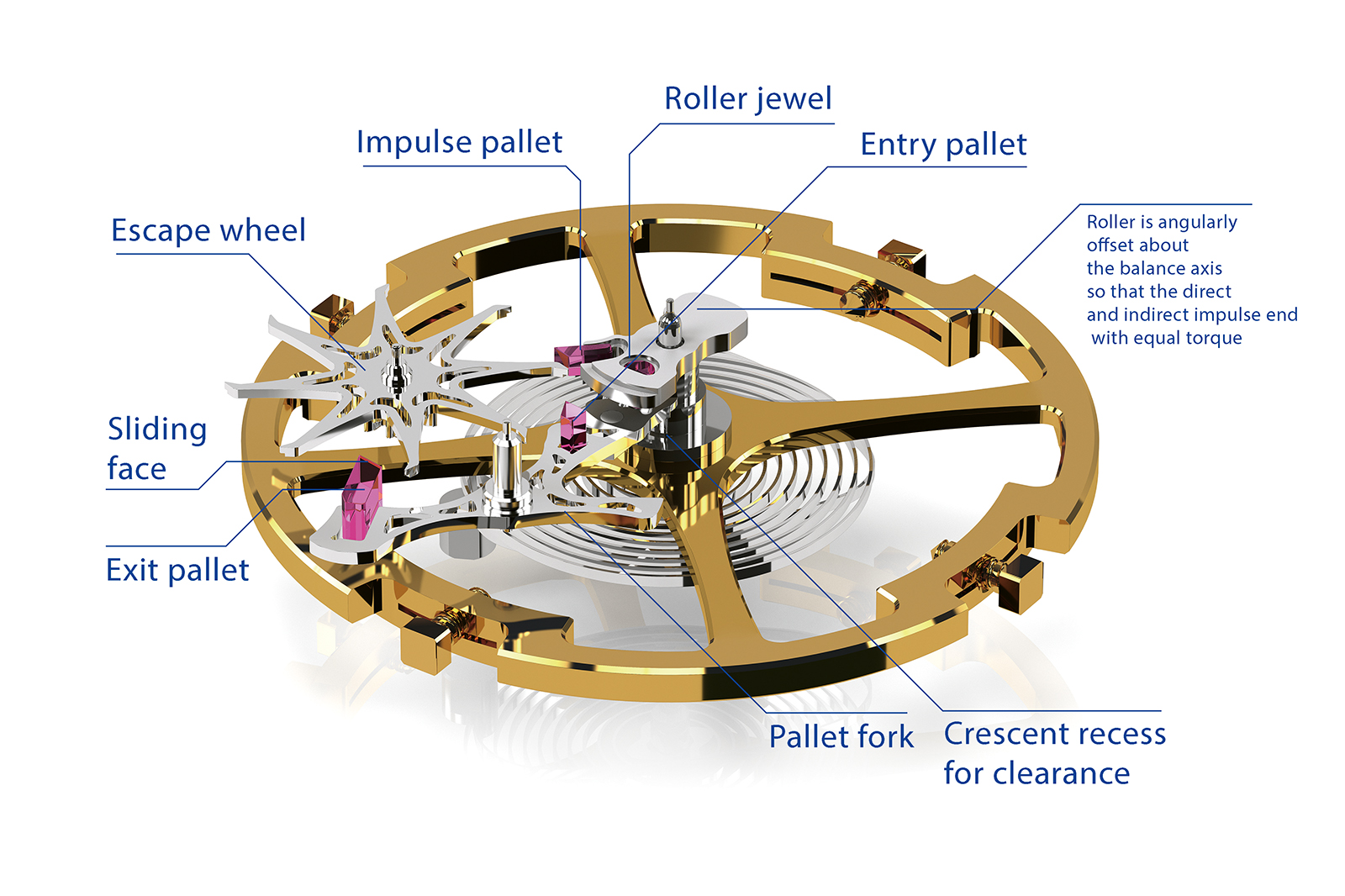

The Grand Seiko Dual Impulse Escapement was designed specifically to address this and ensure that the torque margin at the end of each impulse is equalized. The novelty lies in the geometry of the balance roller fixed co-axially to the balance wheel. The escapement keeps the general architecture of the Swiss lever with two standard pallets for locking and unlocking but modifies the balance roller. The latter carries two jewels: a roller jewel that engages the pallet fork and a direct impulse jewel that can be struck by the escape wheel teeth.

On the balance staff itself is a safety flange with a crescent recess. This flange replaces the conventional safety roller of a Swiss lever. Its cylindrical surface normally blocks the fork horn, preventing the pallet fork from slipping across when the roller jewel is not engaged. Only when the roller jewel is in the pallet slot does the horn align with the crescent recess, allowing the fork to pass freely. In this way, the flange prevents accidental unlocking, while the recess provides the necessary clearance for correct impulse.

The pallet fork pivots about its arbor and consists of a fork body with two arms joined by a central hub, plus a positioning tail. On one arm sits the entry pallet, mounted in a jewel hole, and the roller jewel slot between a pair of dovetails, where the roller jewel engages. The fork horn projects alongside to interact with the flange. On the opposite arm sits the exit pallet, mounted in a slit. Each pallet has flat engagement faces, and the exit pallet also has an additional sliding face. The fork is stopped and positioned by a single banking pin, which limits its swing in both directions.

A closer look at the unusual roller table that carries both the jewel engaging the pallet fork and the direct impulse pallet, while the safety flange below it, cut with a crescent recess, manages clearance

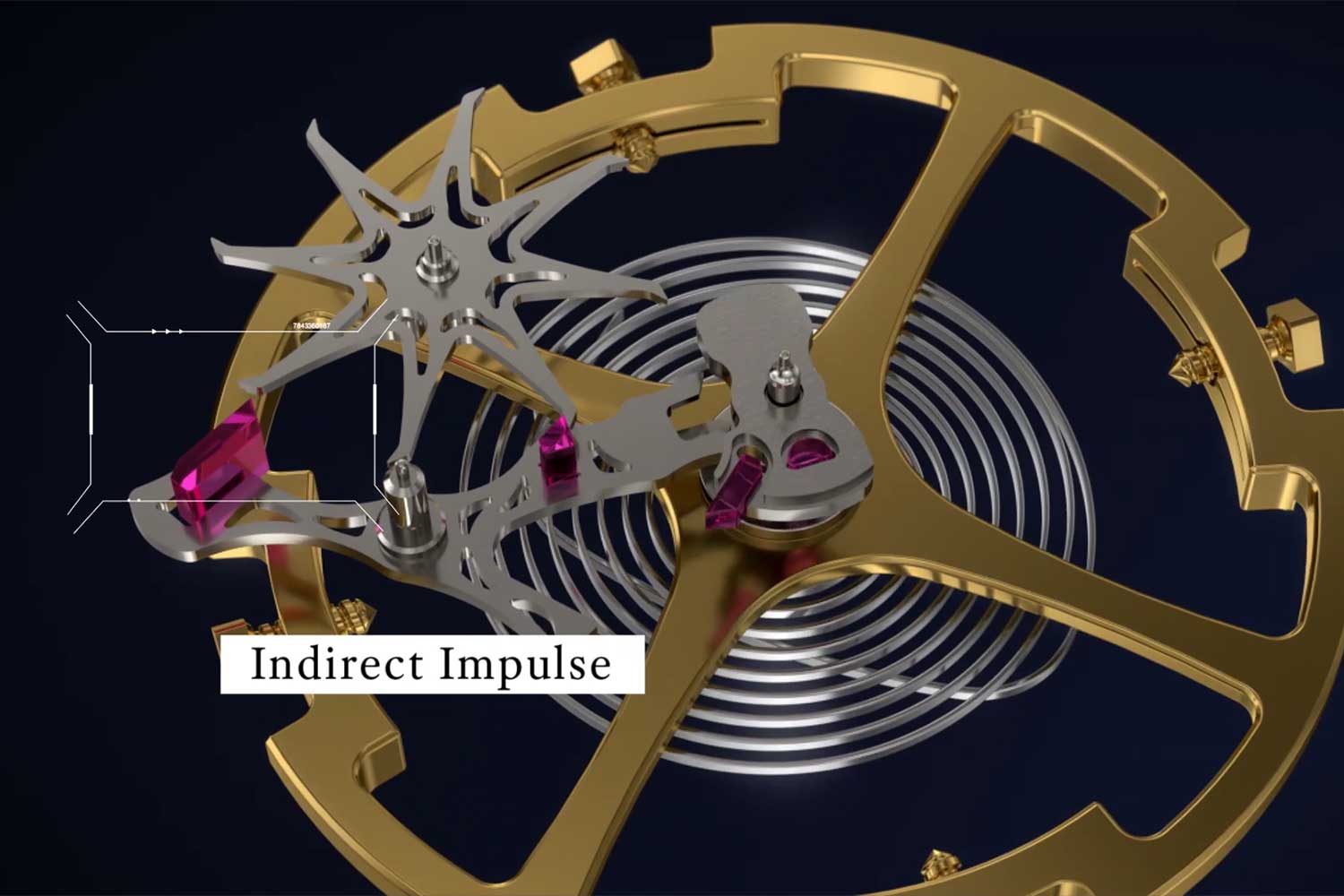

On the forward swing, the escape tooth unlocks from the entry pallet, strikes the impulse jewel, delivers a direct impulse to the balance, and then locks on the exit pallet. On the return swing, the tooth unlocks from the exit pallet, runs along the sliding surface to transmit an indirect impulse via the roller jewel to the balance, and then locks on the entry pallet. The impulses alternate each half-cycle, so over a full cycle, the balance receives one direct and one indirect impulse.

After the indirect impulse, which occurs while the escape wheel tooth slides on the sliding surface of the exit pallet, the escape wheel locks on the entry pallet

The geometry of the roller is unusual. Its center, when viewed from above, is not exactly on the line connecting the balance axis and the pallet fork axis, but offset by a small angle. This offset alters the leverage of the impulses. The indirect impulse (tooth against the exit pallet, through the fork and into the roller jewel) has more links and more angular transmission than the direct impulse. That means a small change in the angle of action greatly affects how much torque is available at the end of the contact. Without offset, the geometry puts this impulse at a disadvantage. As barrel torque declines, the restoring torque of the hairspring overtakes it sooner.

By lengthening the torque arm, shifting the line of action so that the tooth pushes the pallet at a slightly more favorable angle relative to the balance axis, the offset increases the effective lever moment of the indirect impulse. This compensates for its inefficiency, allowing it to carry further into the balance’s swing and finish at the same torque level as the direct impulse. At the same time, it shortens the torque arm of the direct impulse, where the escape wheel tooth strikes the impulse jewel. In the uncorrected geometry, this path is the stronger of the two, because the wheel tooth acts tangentially to the balance roller with very little mechanical loss. By trimming its leverage slightly, the offset ensures that the direct impulse no longer runs on into a region where it would dominate, but instead expends its torque on the same footing as the indirect one.

Additionally, because the roller jewel is intentionally offset, the escape wheel tooth tends to come to rest tangentially on the direct impulse face. When the watch is wound from a complete stop, the escape wheel pushes the impulse jewel and nudges the balance out of its offset equilibrium. With very little starting torque, that first shove often isn’t enough to drive a proper indirect impulse through the fork. Hence, it requires greater torque to self-start. This is less apparent in the self-winding 9SA5, because as the rotor turns, it provides the necessary nudge to restart the escapement, but with the 9SA4, the mainspring has to be wound to a certain degree or the watch needs a gentle nudge to kickstart the escapement. This can also be achieved by closing the crown.

In other words, the escapement imposes a higher threshold at the instant of restart, yet once in motion, this same geometry allows it to sustain oscillation further into the decline of barrel torque. In practice, the watch delivers stable timekeeping deeper into its power reserve, with greater efficiency per unit of torque. It is a design that asks more of the escape wheel in one moment, in order to give more back to the balance over the full course of the run.

The escapement was also optimized for a high-beat 5Hz oscillator. Its components are fabricated using MEMS (micro-electromechanical systems), a lithography process that achieves extreme precision while permitting intricate, skeletonized geometries. This reduces inertia and allows the escape wheel and lever to accelerate more rapidly.

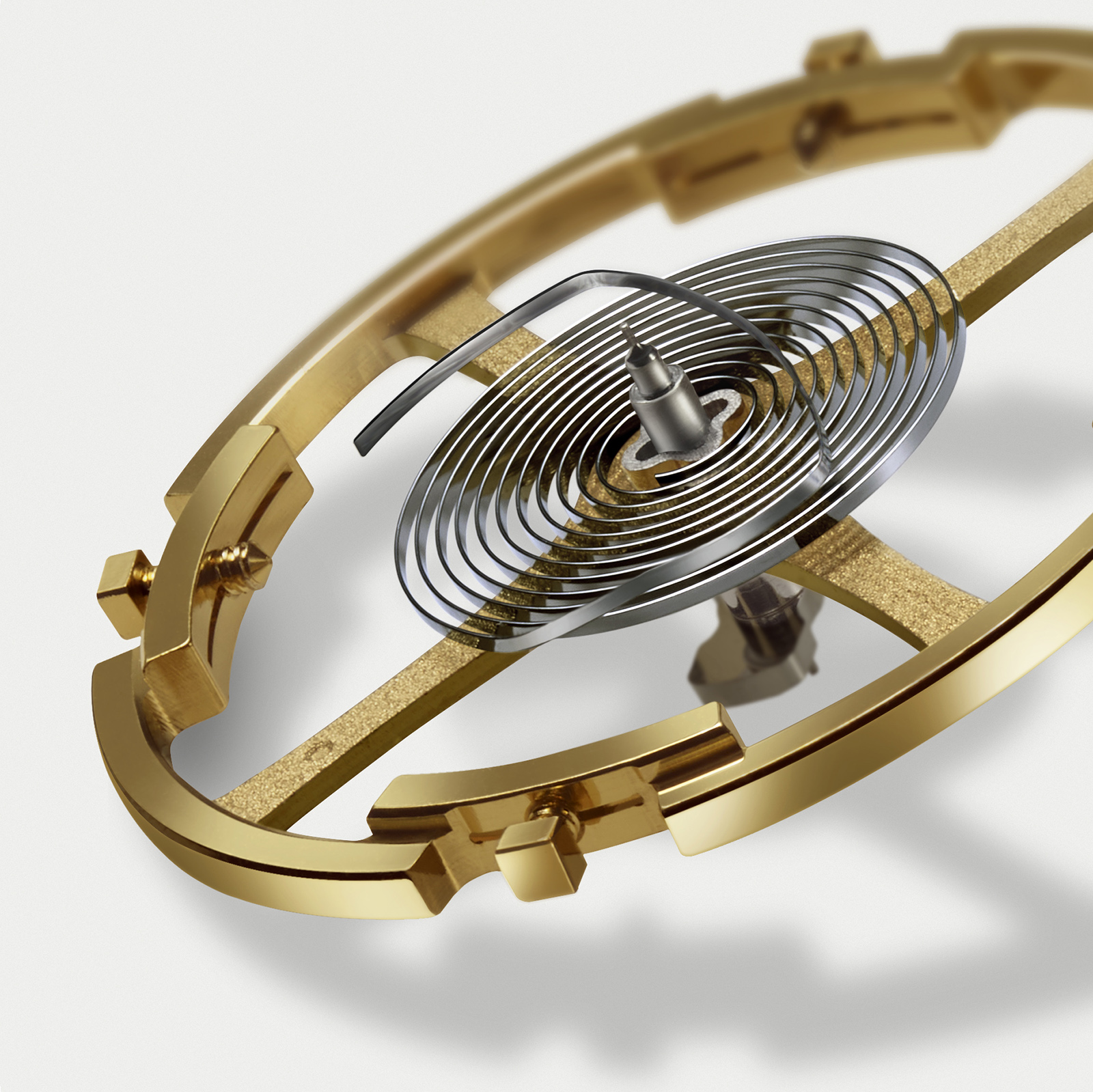

The oscillator itself represented a series of firsts for Grand Seiko. The balance is free- sprung, with four recessed screws set into its rim. It is secured by a full bridge for stability at both ends, a construction otherwise found only in the smaller 9S27. It also uses an overcoil hairspring. The difficulty of shaping each spring by hand has made the overcoil a rarity in modern series production, yet Grand Seiko went so far as to design its own curve, arrived at through more than 80,000 simulations. This is where the mechanism becomes especially meaningful. The stud at the outer terminal of the hairspring is held inside a cylindrical carrier that can rotate around its own axis. When the watchmaker turns this carrier, the stud and therefore the entire overcoil terminal rotates in a controlled arc. This allows the terminal curve of the overcoil to be tuned by rotation alone, rather than by physically bending the spring.

The free-sprung balance is attached to an overcoil hairspring with a very specific terminal curve that was optimized through 80,000 simulations to minimise positional error and maximise isochronism

The stud at the outer terminal of the hairspring is held in a cylindrical carrier that can rotate about its own axis, so turning the carrier rotates the entire overcoil terminal in a controlled arc (©Revolution)

The Movement Architecture

Both the 9SA4 and the 9SA5 are equipped with double, serially coupled barrels that provide a power reserve of 80 hours. An intermediate wheel was introduced into the going train between the fourth wheel and the escapement to distribute the load, rather than increasing the number of teeth on the escape wheel to achieve a higher beat rate. Thinness was clearly a focus, with 9SA4 measuring just 4.15mm in height and the 9SA5 coming in at 5.18mm. This is achieved by ensuring the two barrels are geared directly to each other by their toothed drums and that the center wheel does not overlap the barrel.

To reduce height, the gear train is laid out horizontally in the movement. An intermediate wheel is positioned between the barrel and the offset center wheel to prevent overlapping

Instead of driving the center wheel straight off a barrel, the design routes power through an intermediate wheel. This idler doesn’t change the overall ratio but sets the diameter and rotation sense to allow the center wheel to sit clear of the barrels and be made smaller, supporting the slim profile. The entire gear train is arranged horizontally across the movement with the fourth wheel in the middle to drive the central seconds. As these movements were intended to keep very accurate time, there is also a hacking function.

In the Caliber 9SA4, the hand-winding train is redesigned so that the barrel arbor advances further per crown turn, approximately 15 percent more than in the 9SA5. This is accomplished chiefly by reducing the ratchet wheel diameter to accommodate the relocated click and adjusting the intervening winding wheels accordingly. The barrels and total reserve are unchanged; only the winding ratio differs. The winding torque per turn is thus firmer, and this contributes to the winding experience. The click sounds and feels incredible, making winding the watch a visceral pleasure. Shaped like a wagtail, it is perched on the rim of the ratchet wheel and held by a screw, while its beak touches the ratchet teeth with a curved spring bearing on its back. It rides along an elongated slot and produces a distinctly tactile, visual, and audible winding action.

The 9SA4 also features a fan-shaped power reserve indicator on the back of the movement, just below the winding train. To keep its differential compact within the available lateral space, it uses numerous small-diameter wheels that form two input trains and an output train ending in a tiny sector rack. Their jewels appear on the barrel bridge as a little constellation of red bearings clustered near the center. It’s a quirk that is hard not to find charming once you notice it.

To fit within a remarkably tight space, the power reserve differential train is composed of numerous small-diameter gears, each with a tooth profile designed to improve transmission efficiency

Their jewels appear on the barrel bridge as a little constellation of red bearings clustered near the center (©Revolution)

To improve efficiency, a new tooth profile was developed for the wheels in the power reserve train. During my visit, Yuya Tanaka explained that Grand Seiko designs its gear profiles entirely in-house, without reference to the standard tables used in Swiss watchmaking, and since there are no standard tables in Japan, tooth geometry differs from brand to brand. Given the number of wheels in the power reserve train, assembly is more challenging as all the pivots have to fall into their jewels at the same time, yet, as I got to witness, the skilled watchmakers at Grand Seiko perform this very task in a single, swift motion.

The recently launched Grand Seiko SLGW007 “Moonlit Birch” in stainless steel with a midnight blue dial (©Revolution)

The 9SA4 has so far appeared in only a handful of models, most recently the SLGW007 in stainless steel. At this price point, there is no shortage of time-only or time-and-date watches, but few can truly compete in aesthetics, quality or substance. You can tell a great deal about a watchmaker from its fundamentals. For Grand Seiko, those fundamentals of beauty, precision and a long power reserve are goals that seem disarmingly simple, but which in practice are anything but, and in reaching them, it sets a standard that leaves it alone in its class.

Grand Seiko